Broken Compounder or Rare Sale? Constellation Software Stock Explained

Get smarter on investing, business, and personal finance in 5 minutes.

Stock Breakdown

For years, investors viewed this business as one of the highest-quality compounders in public markets: exceptional capital allocation, durable moats, and a long record of high returns on invested capital.

Then the stock fell nearly 50%, and sentiment flipped sharply, at times to the point where the market began pricing the company as if its best days were behind it.

That reaction may be excessive, but the drawdown is real.

The stock is down roughly 47% from its peak, by far the largest decline in its history and materially worse than its prior maximum drawdown of approximately 30%.

Importantly, the selloff has not been driven by a collapse in fundamentals. If anything, the financial performance has remained resilient.

The company is Constellation Software.

Even after the decline, it remains a roughly 150-bagger since its 2006 IPO, and it has been led for decades by Mark Leonard, often described as the “Warren Buffett of Canada.”

That comparison is frequently overused in markets, but Constellation is one of the rare cases where the label captures something meaningful: a disciplined, repeatable acquisition engine that compounds capital by recycling cash flows into additional purchases.

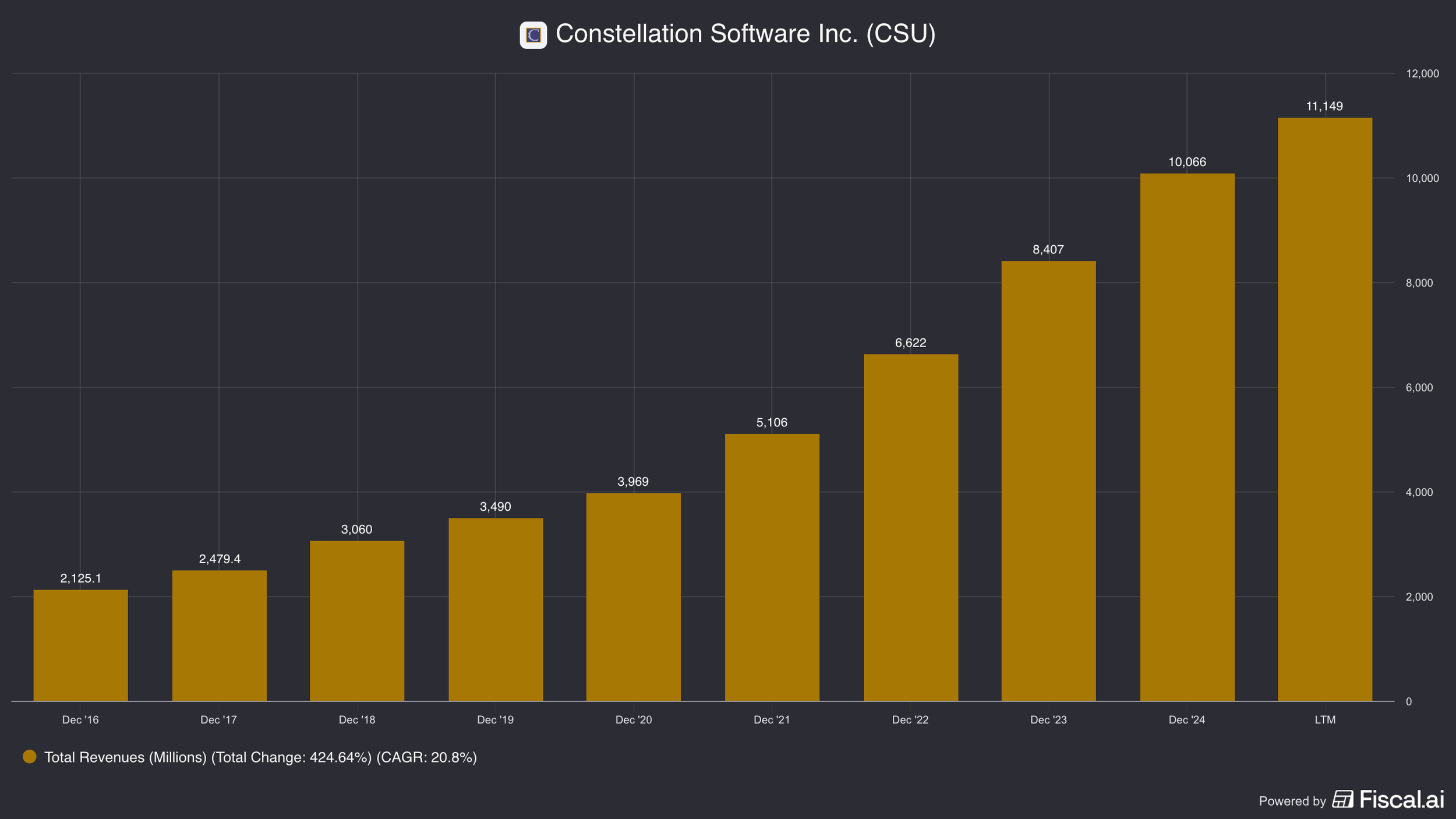

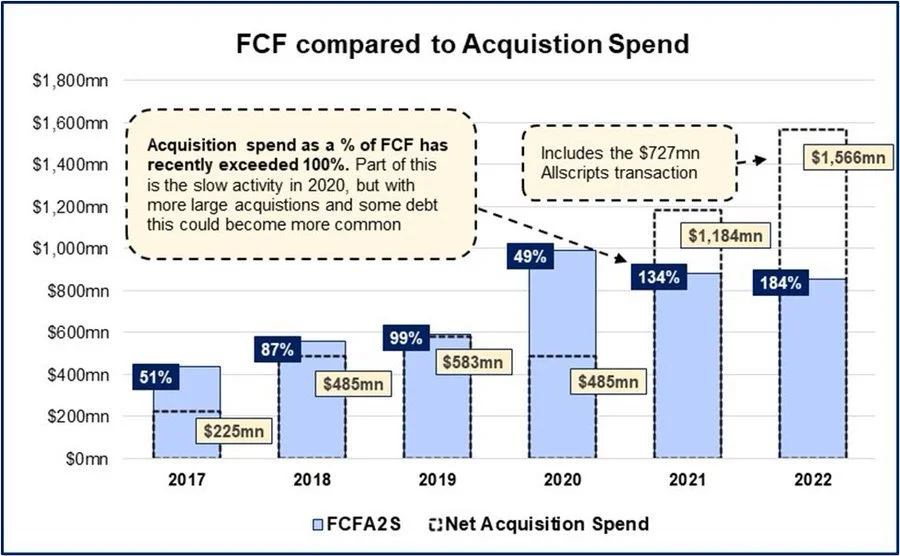

Over the last decade, Constellation has grown revenue at roughly an 20% rate, with free cash flow expanding at a similar pace.

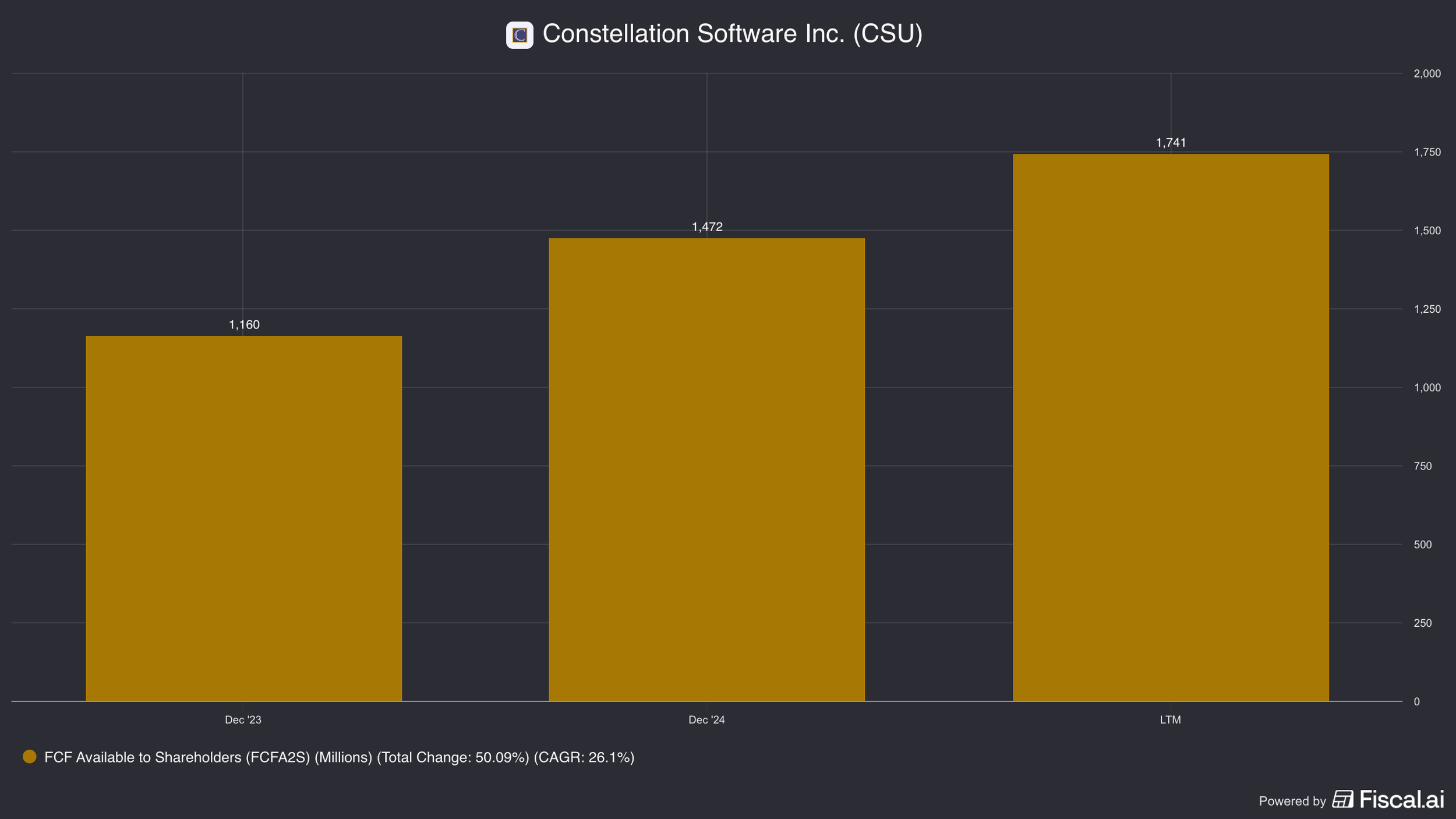

More recently, free cash flow has accelerated sharply, from about $1.1bn in 2023 to a little over $1.7bn over the last twelve months, even as investor sentiment has deteriorated to what appears to be an all-time low.

Free cash flow is actually higher than it appears at a little over $2 billion, because of an adjustment (IRGA liability).

So what’s driving the disconnect?

Two issues dominate today’s bear case:

1) AI risk: the fear that software is becoming easier to build and therefore easier to displace.

2) The leadership transition following Mark Leonard stepping down.

Both have raised legitimate questions.

But neither automatically implies a deterioration in Constellation’s underlying model.

The Constellation Model.

Constellation was founded in the early 1990s after Leonard observed a persistent market inefficiency:

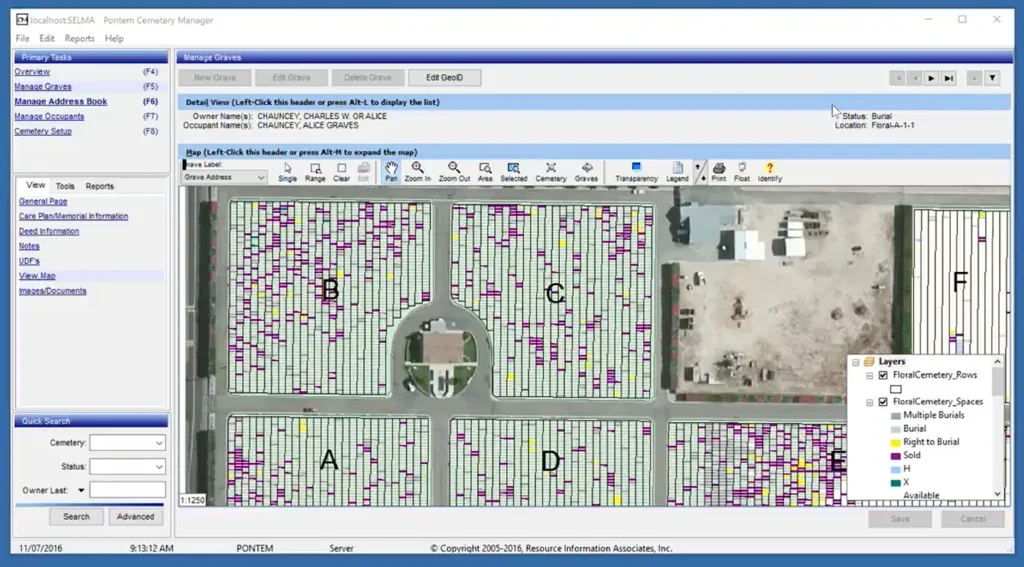

Vertical market software businesses often have highly recurring, mission-critical revenue, but limited standalone growth and small total addressable markets, frequently only a few million dollars in annual revenue.

That combination made them unattractive to venture capital and too small for most private equity funds, which left a thin buyer universe and depressed valuation multiples.

Mark Leonard’s insight was to buy these businesses at conservative multiples and redeploy their cash flows into additional acquisitions.

At the operating company level, moats are typically stronger than they appear.

These systems are deeply embedded in workflows, customized over time, and integrated into surrounding processes.

Switching is not just expensive, it’s operationally disruptive. In many cases, the most common source of churn is not competitive displacement but customer failure (ie. bankruptcy).

At the holding-company level, however, the moat is different.

Mark Leonard has long acknowledged that the barriers to entry in acquisition-led software are not structural, anyone can theoretically compete with “a phone book and a checkbook.”

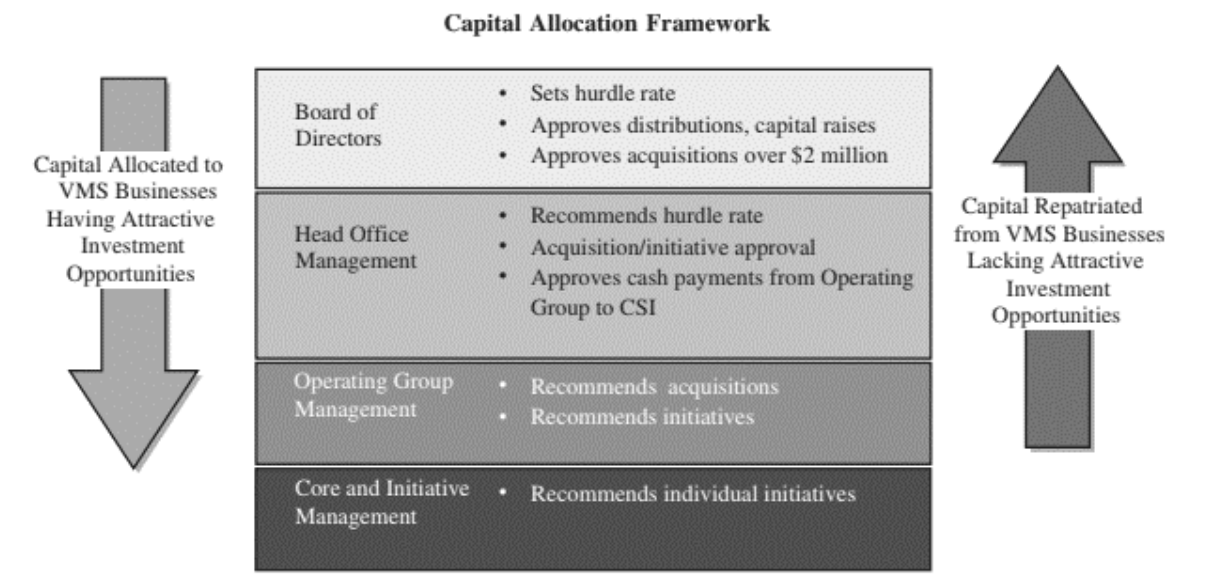

Where Constellation differentiates is in execution: proprietary deal flow cultivated over decades, high-quality stewardship that appeals to founder-owners, and a decentralized capital allocation system that pushes decision-making down to business units while enforcing hurdle rates.

Reinvestment Runway.

Even before AI entered the conversation, the core strategic risk was straightforward: as Constellation grows, it must continuously find enough opportunities to redeploy capital at attractive returns.

With free cash flow now above $2bn, the company needs either a very high volume of small acquisitions or periodic larger deals to maintain its historical deployment pace.

That is why the company’s more recent shift toward larger transactions matters.

Deals like Allscripts (~$700mn) create a more efficient pathway to put capital to work and extends the reinvestment runway.

The key question for an investor to ask is not whether Constellation can keep buying companies—it almost certainly can—but whether it can do so while maintaining discipline and historical return hurdle rates as deal sizes increase.

AI Risk.

The AI bear case is intuitive: if software becomes easier to create, competition rises, and incumbents lose pricing power or retention.

In vertical market software, however, this framing often misses the real drivers of customer behavior.

The competitive advantage in these markets has never been that software is hard to build.

Many vertical systems are not technically complex, and a motivated team could build a cleaner UI or replicate core functionality without Ai.

Yet disruption has historically been rare because the customer’s incentives are asymmetric: the software already works, the cost is often small relative to the business, and the downside of switching is operational failure.

A modestly better interface or a slightly cheaper price rarely clears the “worth the pain” threshold.

VC investor Peter Thiel stated in his book Zero to One that you can't really disrupt an incumbent unless you come out with something that is 10x better. So if the Ai vertical software is not 10x better, people are not going to go through the hassle of switching.

Even more importantly, vertical software is not just code, it is implementation, support, integrations, and reliability.

Customers care less about how the tool was created and more about whether it will run their business without interruption.

For mission-critical workflows, “99.9% reliable” can still be unacceptable if failures occur in the wrong moment and there is no accountable support organization behind the product.

If anything, Ai may disproportionately benefit incumbents like Constellation, which already own the distribution, data, and embedded customer relationships.

If Ai meaningfully improves product iteration or service delivery, Constellation is positioned to adopt it across hundreds of niche platforms, and potentially improve organic growth at the margin.

Leadership Transition.

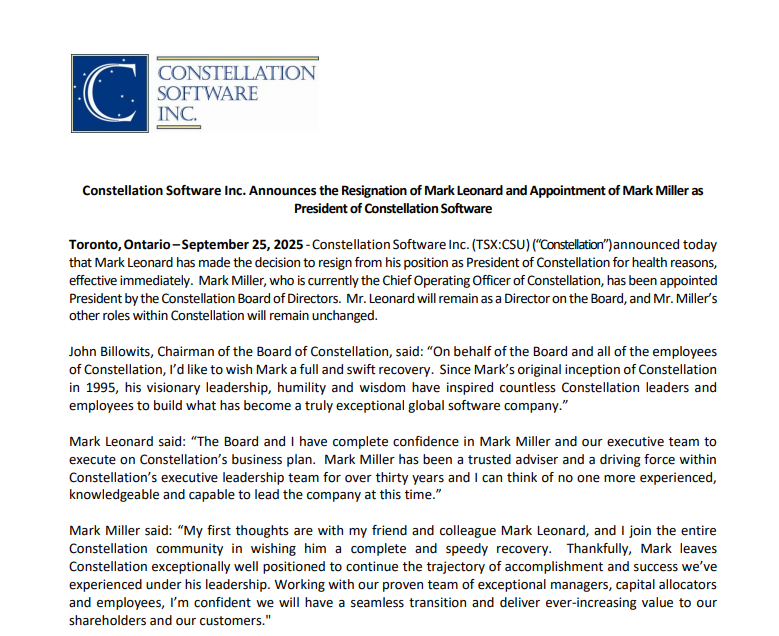

The second driver of sentiment has been the CEO transition.

Mark Leonard stepping down shortly after an Ai-focused discussion created poor optics, particularly given the company’s historically minimal investor communication.

However, Constellation’s operating model is notably decentralized.

Capital allocation decisions are distributed across operating groups and business units, with headquarters primarily involved in the largest transactions.

This structure reduces key-person dependency relative to more centralized models.

Mark Miller, the new CEO, is not an outsider.

He has been with the company since the mid-1990s and has been deeply involved through multiple cycles and strategic transitions.

The more relevant question is not whether leadership has changed, but whether Constellation’s culture of discipline and decentralized decision-making remains intact.

Market Debate.

At today’s level—trading around ~19x free cash flow—the stock appears to be reflecting skepticism that Constellation can't sustain historical rates of return amid (1) the perceived Ai disruption risk and (2) uncertainty tied to leadership change.

The counterpoint is that fundamentals, particularly cash flow, have improved, and that the acquisition engine remains functional.

Ultimately, the question is whether you as the investor believe the newly perceived risks are transient noise or a genuine blow to the durability of the model.

For more on Constellation Software, check out this video below.

Nothing in this newsletter is investment advice nor should be construed as such. Contributors to the newsletter may own securities discussed. Furthermore, accounts contributors advise on may also have positions in companies discussed. Please see our full disclaimers here.