Every Valuation Is a DCF (and 5 Ways to Make Yours Make Sense)

Get smarter on investing, business, and personal finance in 5 minutes.

Every Valuation Is a DCF (and 5 Ways to Make Yours Make Sense)

Despite what you may think, there is only one valuation method.

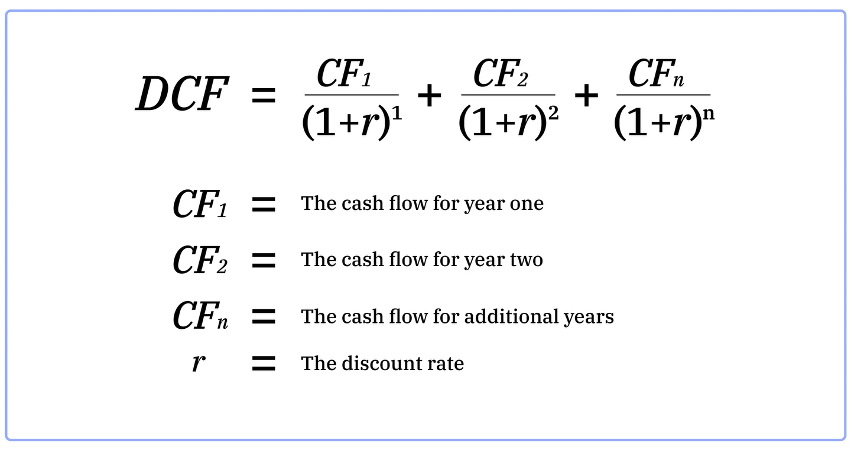

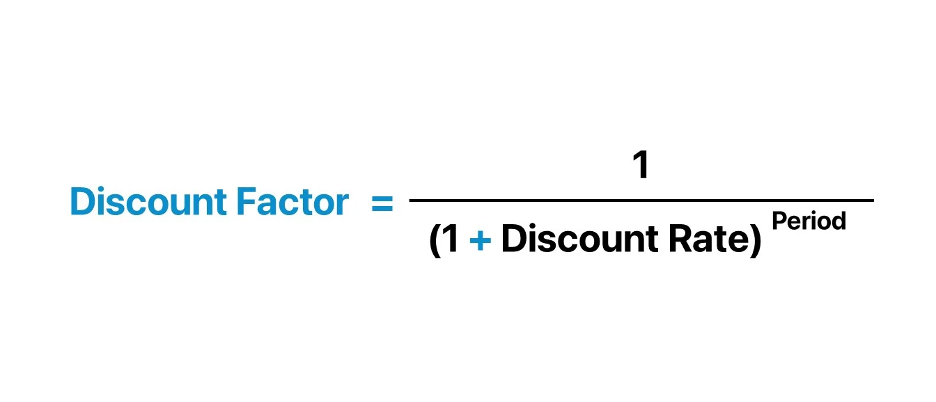

That is the DCF or discounted cash flow model.

All other valuation methods are just a shorthand for this method.

The reason why is simple:

Investing is simply giving up money now in order to have more money in the future.

The DCF is the only way to actually know how much that “future money” is worth today.

Now some may object that a lot of great investors like Warren Buffett don’t use DCFs. Are you saying Warren Buffett isn’t investing?

It’s true.

Warren Buffet never uses Excel and can do all of his math on a napkin (actually he usually does it in his head).

But the valuation math he is doing is basically a short-cut for a DCF.

That’s what makes it investing!

In fact, all “valuation methods” are essentially DCFs.

Allow me to explain.

Why a multiple is a Shorthand for a DCF

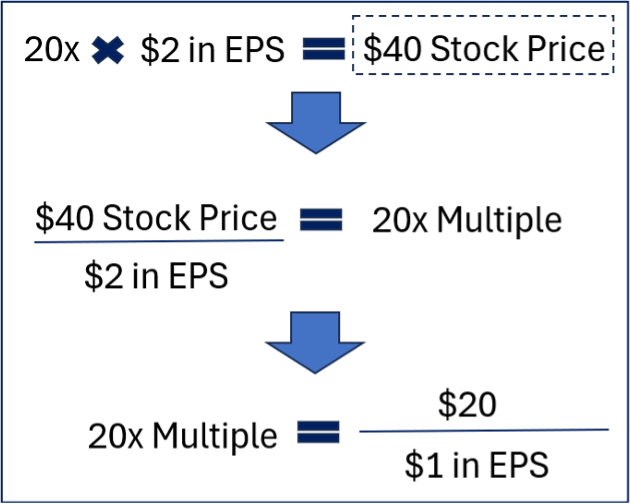

One of the most common ways to value a stock is by applying a multiple of earnings or cash flows.

An investor may say, “this stock is worth 20x”.

If the company had $2 in earnings per share (EPS), then that stock would be worth $40.

You can see the relationship simply below.

When you think about what a multiple is, all you are saying is “I’m paying X dollars today for $1 of current earnings.”

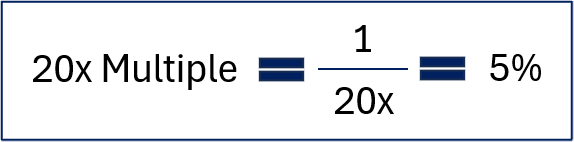

Now, how is this a DCF though?

Let’s invert this 20x. Now it is a 5% earnings yield.

When you pay 20x for a stock, you are saying the same thing as “I am willing to accept a 5% earnings yield”.

A 5% return though isn’t that good for most investors.

So why are they okay with this?

That is where growth comes in.

Most investors want at least a 10% return.

The way they get there is with future growth in earnings.

So in 10 years that $1 of earnings maybe grows to $4.

Now only your original 20x multiple is 5x. And that earnings yield increases to 25%.

Now that questions of (1) how much a stock needs to grow that $1 of earnings and (2) how quickly is EXACTLY what a DCF answers.

An investor only pays 20x for a stock because they think it will grow more in the future.

This is the same math Warren Buffett is doing in his head.

Buffet talks about how he looks for at least a 10% pre-tax return.

In order to get that, he needs the earnings to grow.

He may buy a stock based on a multiple of earnings, but the math behind it is supported by a DCF.

It is just that Buffett has such a good sense of how a multiple ties to the returns shown in a DCF that he doesn’t need to do it.

In fact, most investors’ problems with the DCF, isn’t the DCF.

The problem is their misunderstanding of how to use it.

They may think it is too precise.

Or you need to make assumptions you can’t possibly know about the future.

Or it only works when a company has predictable cash flows.

This keeps you from benefiting from a DCF.

Below are the 5 common DCF misconceptions and how to fix them.

And until an investor is as good as Warren Buffett, it might be worth considering the DCF.

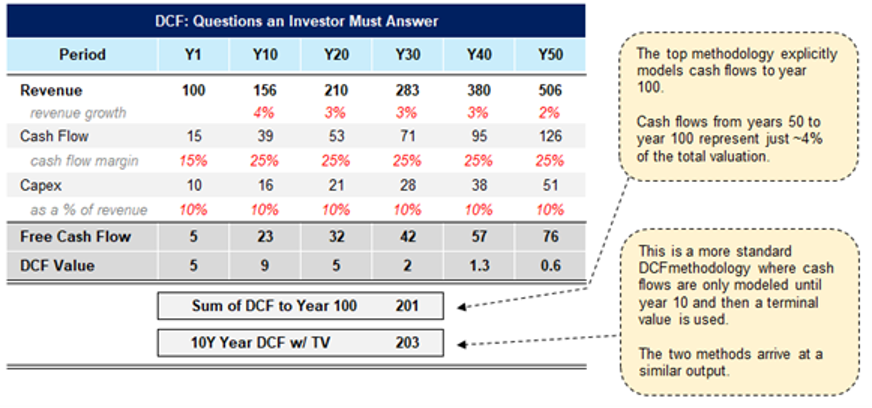

Mistake 1: Don’t Forecast Far Enough

This is the most common mistake.

People forecast five years.

Maybe ten.

Then they complain that the model doesn’t make sense.

But that was a choice.

If something is growing faster than the economy, it shouldn’t magically stop in year five.

You can forecast 20 years.

50 years.

Even longer.

Excel doesn’t care.

And here’s the important part:

The further out you go, the less those cash flows matter.

They’re discounted more heavily.

So uncertainty far in the future doesn’t break the model.

It weakens its impact.

That’s a feature.

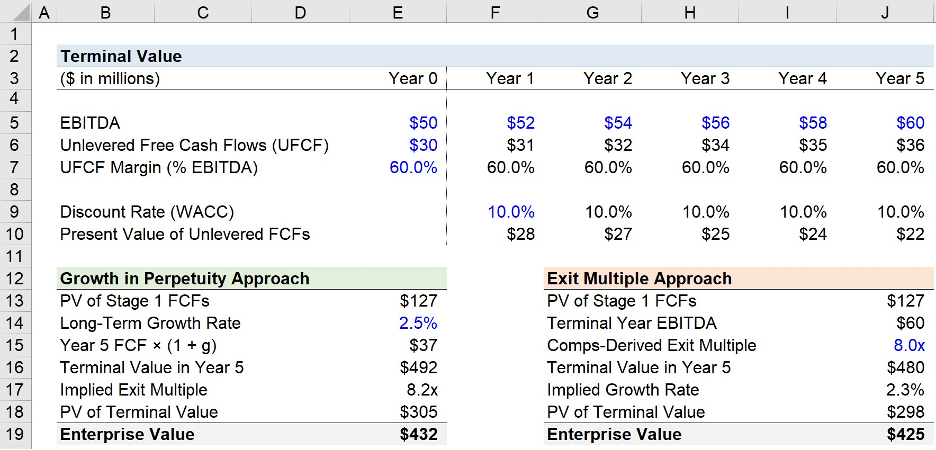

Mistake 2: Terminal Value

Terminal value isn’t mandatory.

It’s a shortcut.

Most people use it because they don’t want to keep forecasting.

But problems arise when terminal value is used too early.

If something is still growing faster than the economy, it isn’t “terminal.”

Forcing a terminal value in year five or ten is saying:

“I don’t know what happens next, so I’ll stop thinking.”

A cleaner approach is simple:

Let growth fade gradually.

Extend the forecast.

Only use terminal assumptions when growth looks truly steady.

Mistake 3: Thinking it’s Too Subjective

Yes, DCFs are subjective.

That’s the point.

If valuation were objective, computers would do it perfectly.

Prices wouldn’t move.

Returns would converge.

But investing is about judgment.

All a DCF does is surface your assumptions:

How fast things grow

How long growth lasts

How profitable things become

How confident you are

If you’re uncomfortable with an assumption, lower it.

That is your margin of safety.

The model isn’t fragile.

Your assumptions are.

And they’re supposed to be.

Mistake 4: Discount Rate

People obsess over this.

“What discount rate should I use?”

In practice, it’s simple:

The discount rate is the return you want.

That’s it.

All the theory exists to justify a number.

But investing isn’t theoretical.

It’s personal.

If you want 10%, use 10%.

If you want 15%, use 15%.

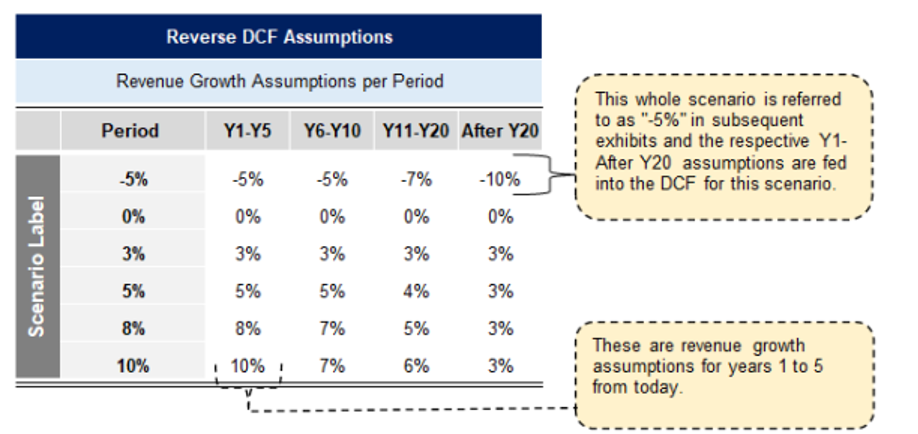

And if you don’t want to choose one at all…

Reverse the process and use the Reverse DCF.

Start with today’s price.

Model reasonable cash flows.

Let the output be the return.

Then ask:

Is this return enough for the risk I see?

That question matters more than the math.

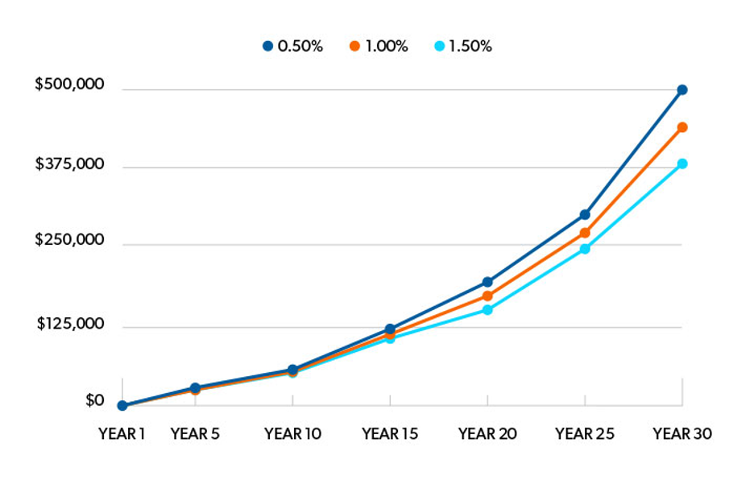

Mistake 5: “It’s Too Sensitive”

This criticism sounds technical.

But it’s actually intuitive.

Small changes in return assumptions create big changes in value.

Why?

Because returns compound over decades.

The same reason:

One extra percent in fees matters

One extra percent in long-term returns matters

The DCF isn’t fragile.

Compounding is powerful.

If you’re wrong by a little for a very long time, the difference becomes large.

That’s not a flaw.

That’s reality.

It’s also why disciplined investors are strict with hurdle rates.

Small compromises today echo for decades.

So is this about being “right”?

No.

It’s about being explicit.

You are always making assumptions in every valuation method.

A DCF just forces you to write them down.

Whether you do that in Excel,

on paper,

or in your head…

you’re still playing the same game.

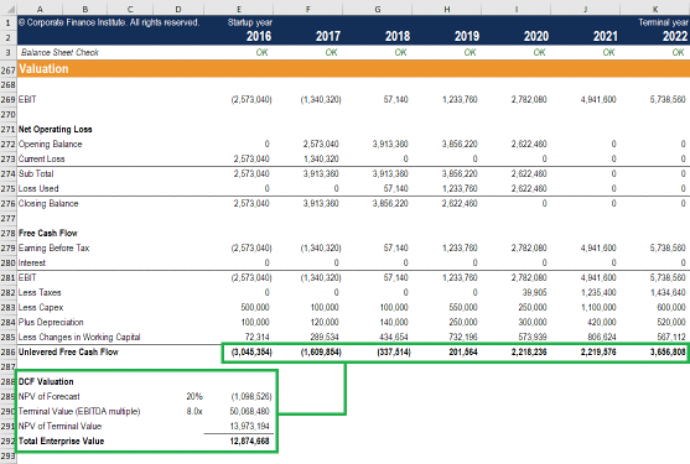

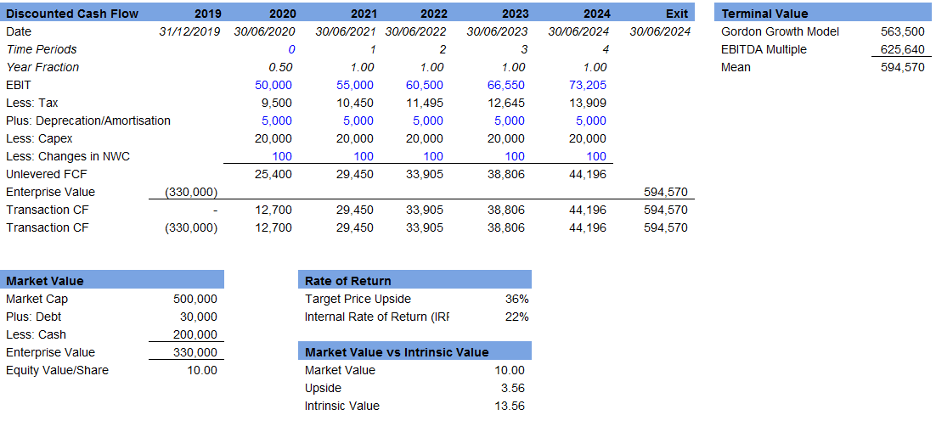

Valuation Walkthrough

Think of it this way:

Paying a high multiple means you need growth to justify the return.

Paying a low multiple means you need less growth.

That relationship never changes.

The DCF simply connects:

Price today

Cash flows over time

Return as the output

You can run one scenario.

Or ten.

Or a hundred.

The math doesn’t care.

It just shows you the consequences.

A DCF is a framework.

It’s a tool.

But it’s in how you use it that dictates how effective it is.

For more on the DCF, check out this YouTube video below.